Thanks to Esther Saoub and Paul Barford amongst others, there have been many updates to the ‘first material proof‘ that Islamic State is trafficking antiquities.

In a further follow-up, I’ve reassessed the balance of antiquities and forgeries. I believe that most of Abu Sayyaf’s stash comprised ancient coins. [I’m working on a huge update based on the U.S. State Department Cultural Heritage Center’s summary and photo gallery of the ISIL leader’s loot.]

Baghdad to Mosul to Deir ez-Zor to where? Baghdad to Deir ez-Zor, Mosul to Deir ez-Zor, Deir ez-Zor to where?

Basics

First, SWR reporter Esther Saoub explained that, though her article was published before his broadcast, the news was Iraqia TV correspondent Amir Musawy’s scoop.

The reported number of recovered objects ranged from more than 70 to more than 400 to nearly 500 [as Paul Barford noticed, to 700 “objects and fragments” to 750 “objects and fragments”]. But the difference seems to be an artificial product of counting sets as sets or as masses of individual pieces. [Update (17th July 2015): even accounting for piece-by-piece counting of sets, how can there be four different counts of those numbers, which vary by 350?]

While it is unclear how many there are or when they will be returned, any Syrian objects will apparently be returned to Syria ‘soon [demnächst]’. How will that happen, since the United States no longer recognises the Assad regime? Is it more optimistic about the prospects of imminent peace or is it going to deliver the antiquities to the opposition coalition?

Too poor to be propaganda?

There are so many holes in the story and loose ends that it is only natural to be suspicious. However, I think that – if it were a U.S. or Iraqi propaganda exercise (beyond PR) – the evidence would have been less rubbish.

There would have been more of the more notoriously sellable “Mesopotamian” (Iraqi) objects. There would have been fewer fragments that are the archaeological equivalent of something only a mother could love. There would not have been a fake Nefertiti…

A paper trail or a dead end?

Loveday Morris noted object codes from the National Museum of Iraq remain on some artefacts; and, as I learned via Paul Barford, Amir Musawy showed that old museum labels appear to have been preserved. However, considering the presence of fakes, the codes and labels themselves will need to be checked to ensure that they were not forged to falsely authenticate the objects.

Still, there appears to be forensic evidence not only for the Islamic State’s handling of illicit antiquities, but also for both the persistence of pre-conflict trafficking structures and the Islamic State’s interlocking with those structures.

Loveday Morris also relayed that “receipts” alongside objects ‘documented illicit sales‘, presumably by documenting sales of undocumented antiquities, a technicality that may be attacked by antiquities trade lobbyists.

Since the receipts went back to the 1980s, Morris considered the possibility that, ‘if they were Abu Sayyaf’s, he may have been in the smuggling game for decades’. Yet, as Paul Barford noted, “Abu Sayyaf” was the nom de guerre of a Tunisian fighter, Fathi ben Awn ben Jildi Murad al-Tunisi. As far as I know, there is no evidence that he was in Syria before the war. Would a smuggler have taken antiquities from Iraq and Syria to Tunisia, not sold them for thirty years, then taken them back with him when he returned as a paramilitary (even as a member of the “officer class” of the paramilitary)?

Moreover, would a mobile terrorist mastermind carry around thirty-year-old antiquities sales receipts, when his potential buyers show so little interest in seeing them in general, let alone acquiring them, in particular when these would either say so little that they were worthless or establish a paper trail to an internationally-wanted terrorist? If the receipts are genuine and the information is accurate, they strongly suggest that this was not Abu Sayyaf’s stash (at least not until very recently).

Was it a cache at a forgery workshop in Syria?

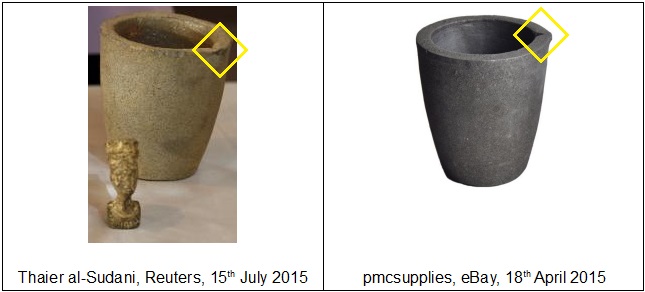

Paul Barford, on Portable Antiquity Collecting and Heritage Issues (PACHI), has done a sterling job of picking out copies, fakes and freaks, from the plaques to the miniature Nefertiti bust to the metal foundry’s smelting crucible.

Recovered artifacts are seen at the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad July 15, 2015

(c) Thaier al-Sudani, Reuters, 15th July 2015 a

A PACHI-inspired comparison of an object photographed by Thaier al-Sudani, Reuters, 15th July 2015 with a crucible auctioned by pmcsupplies, eBay, 18th April 2015

As the head of excavations in Lebanon, Assaad Seif, told the BBC in a separate discussion, their law enforcement agencies had seized most illicit cultural goods from Syria from Islamic State territory, and they had seized hundreds of antiquities but thousands of forgeries.

Is it possible that this was one shipment of material, which included a few genuine articles among a lot of fakes, hence the poor range of poor imitations? Considering the metal-smelting crucible that Paul Barford noticed, is it even possible that Sayyaf’s hideout was a forgery workshop?

Was it a shipment from a forgery workshop in northern Iraq?

Loveday Morris was told that a ‘leather manuscript, written in ancient Aramaic‘, had been ‘seized by US forces during the Abu Sayyaf raid in Syria’ as well. ‘An official at the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad said Wednesday that it was about 500 years old but has not yet been properly dated.’ I think this may be a particularly instructive find.

‘This leather manuscript, written in ancient Aramaic, was seized by US forces during the Abu Sayyaf raid in Syria’

(Loveday Morris, Twitter, 15th July 2015)

It may help to compare it with a Syriac bible that was probably stolen from south-eastern Turkey and smuggled into Cyprus in 2009, which Byzantinologist Charlotte Roueche and Syriac linguist J. F. Coakley thought might be genuine(ly 500 years old, not reportedly 2,000 years old), Biblical scholar James Davila thought might be modern, Aramaic translator Steve Caruso thought was ‘probably either a work no earlier than the 15th century, or a modern forgery‘, and Aramaic and Syriac lecturer David G. K. Taylor judged to be ‘one of a large number of fake Syriac manuscripts currently being produced in northern Iraq and southern Turkey’.

‘Ancient’ Syriac bible found in Cyprus

(c) Sarah Ktisti and Simon Bahceli, Reuters, 6th February 2009

‘Ancient’ Syriac bible found in Cyprus

(c) China Daily, 7th February 2009

The book in Syria has a fairly uniform, deep and wide darkening along the vertical edge of the page, which the book in Cyprus does not. The book in Syria appears to have something like a bullet hole of a cigarette burn. And the “Syrian” book’s painting of a figure with a raised right hand appears to have been reduced to a ghostly stain on the page, whereas the “Cypriot” book’s artwork is still clear.

Furthermore, although it may be a product of translation from Arabic to English or from technical to everyday speech, Steve Caruso specifically listed the fact that a manuscript was written ‘on leather rather than actual vellum’ as a marker of forgery.

Obviously, some – perhaps most – of these objects are genuine antiquities, and some of them can even be traced back to individual episodes of theft. But some of these objects seem to be forgeries. And one of the notorious forgery industries is in the same place as one of the confirmed sites of theft. Could they have been assembled and shipped from Mosul?

Leave a comment